We’ve known for a few years that income correlates with health in a major way. From the length of life to stroke risk to self-reported health status, the more access, opportunity, and means of upward mobility a person has, the better their projected health outcomes.

Waves of organizations are stepping up to help put things on a better course. Accountable and managed care organizations like Upward Health are working with payers, providers, and local governments to bring doctors, nurses, and community health workers to underserved neighborhoods. In some places, networks like L.A. Care have sprung up to give low-income patients affordable access to doctors and hospitals.

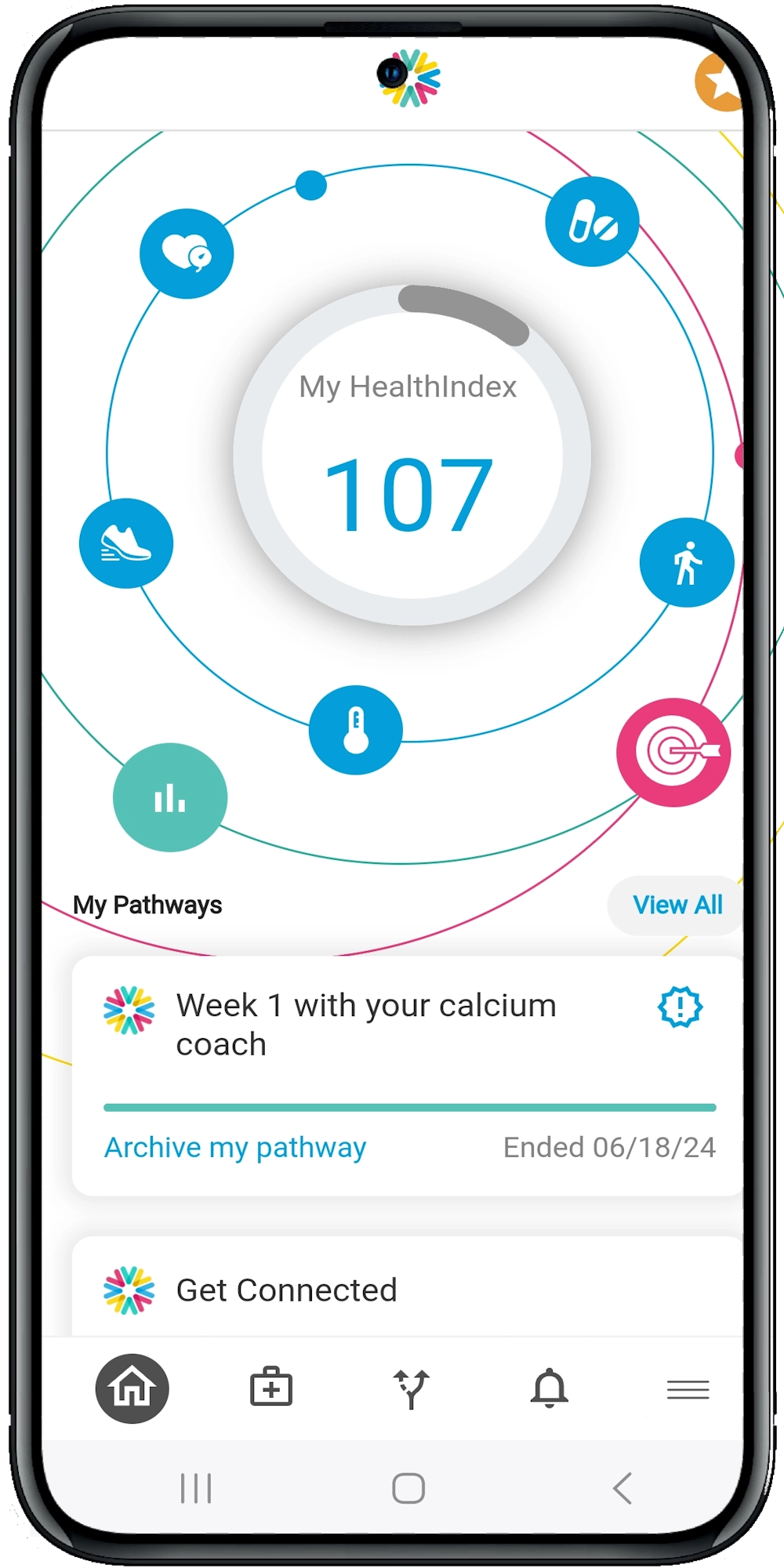

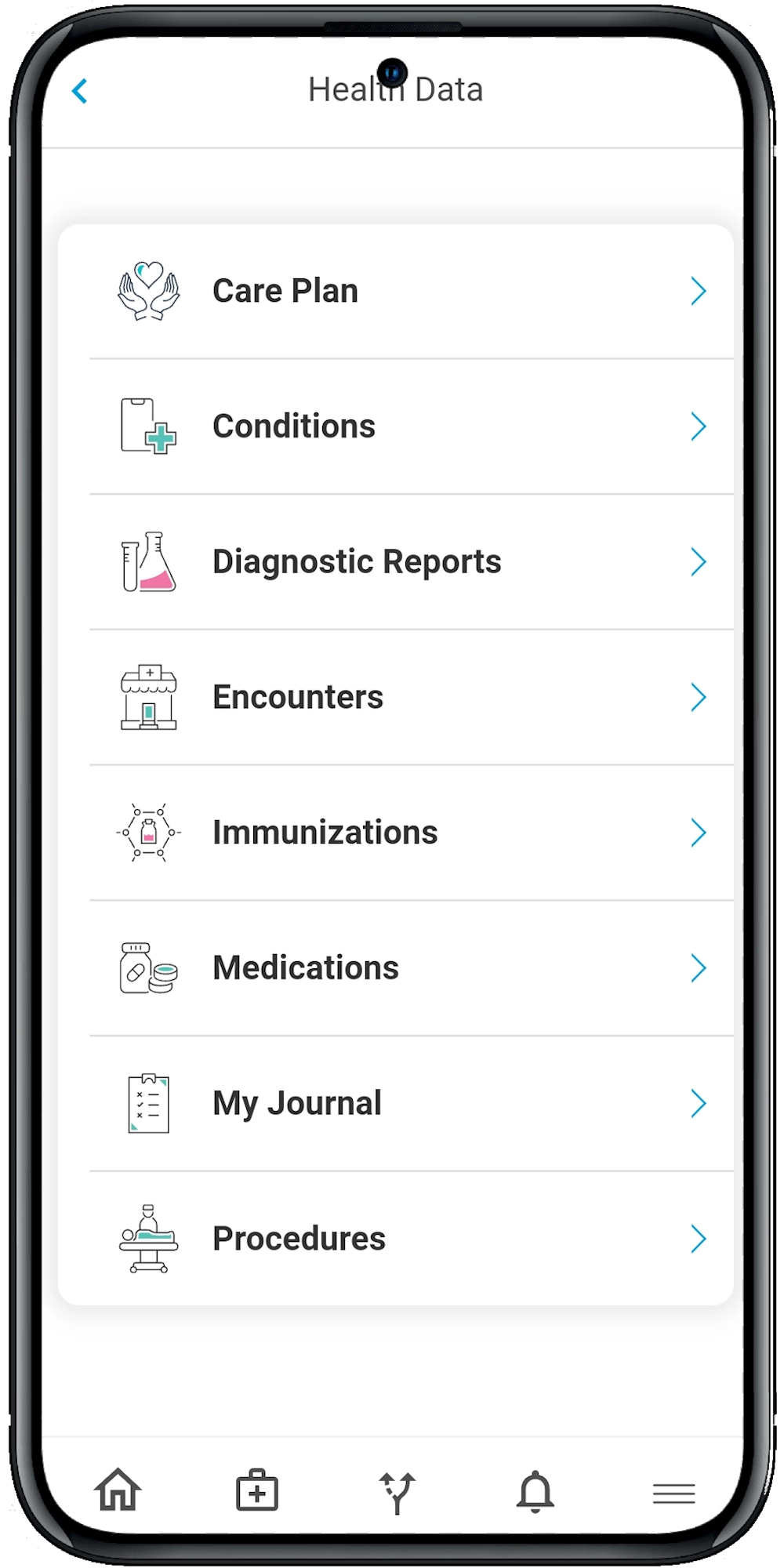

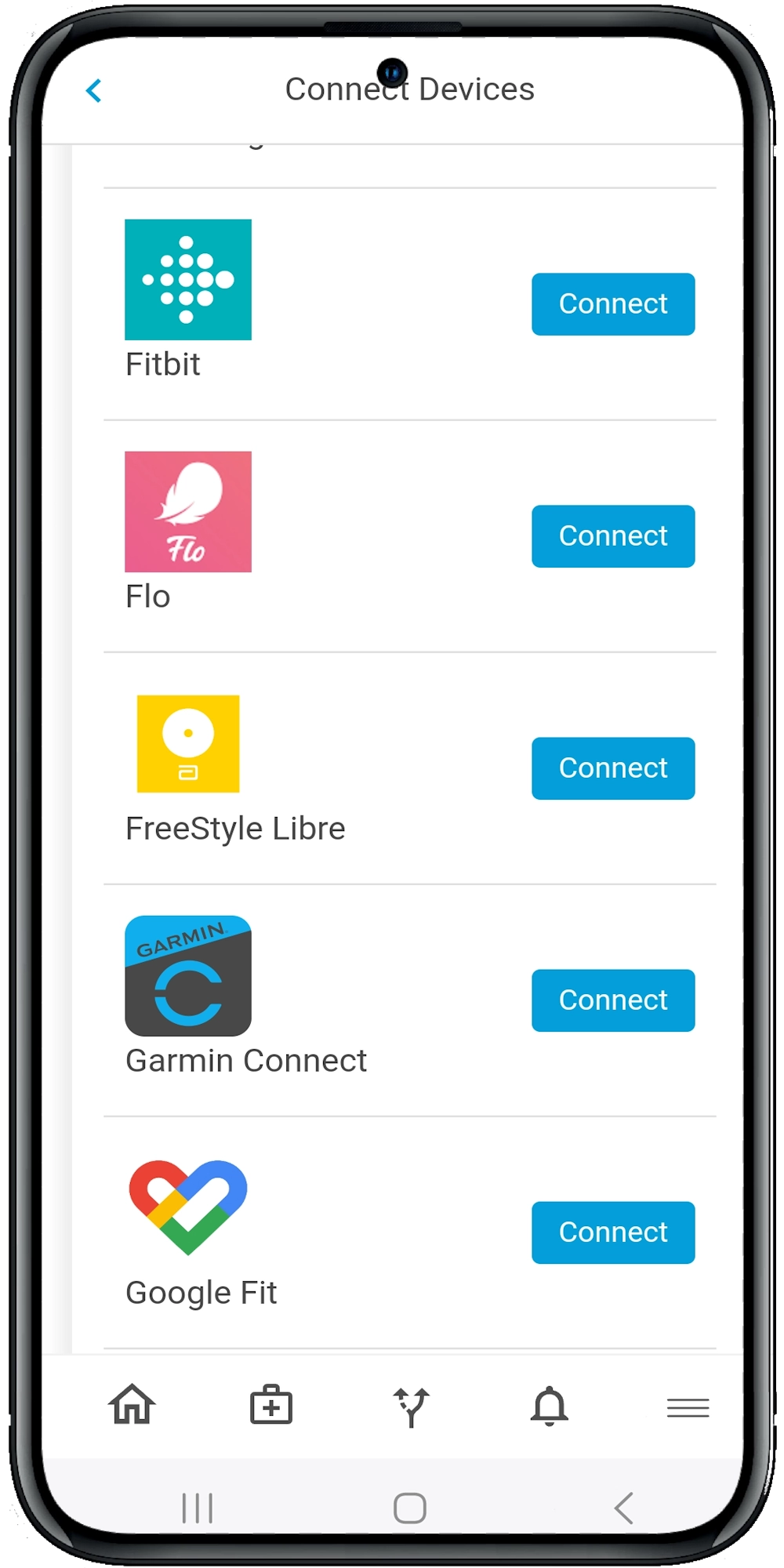

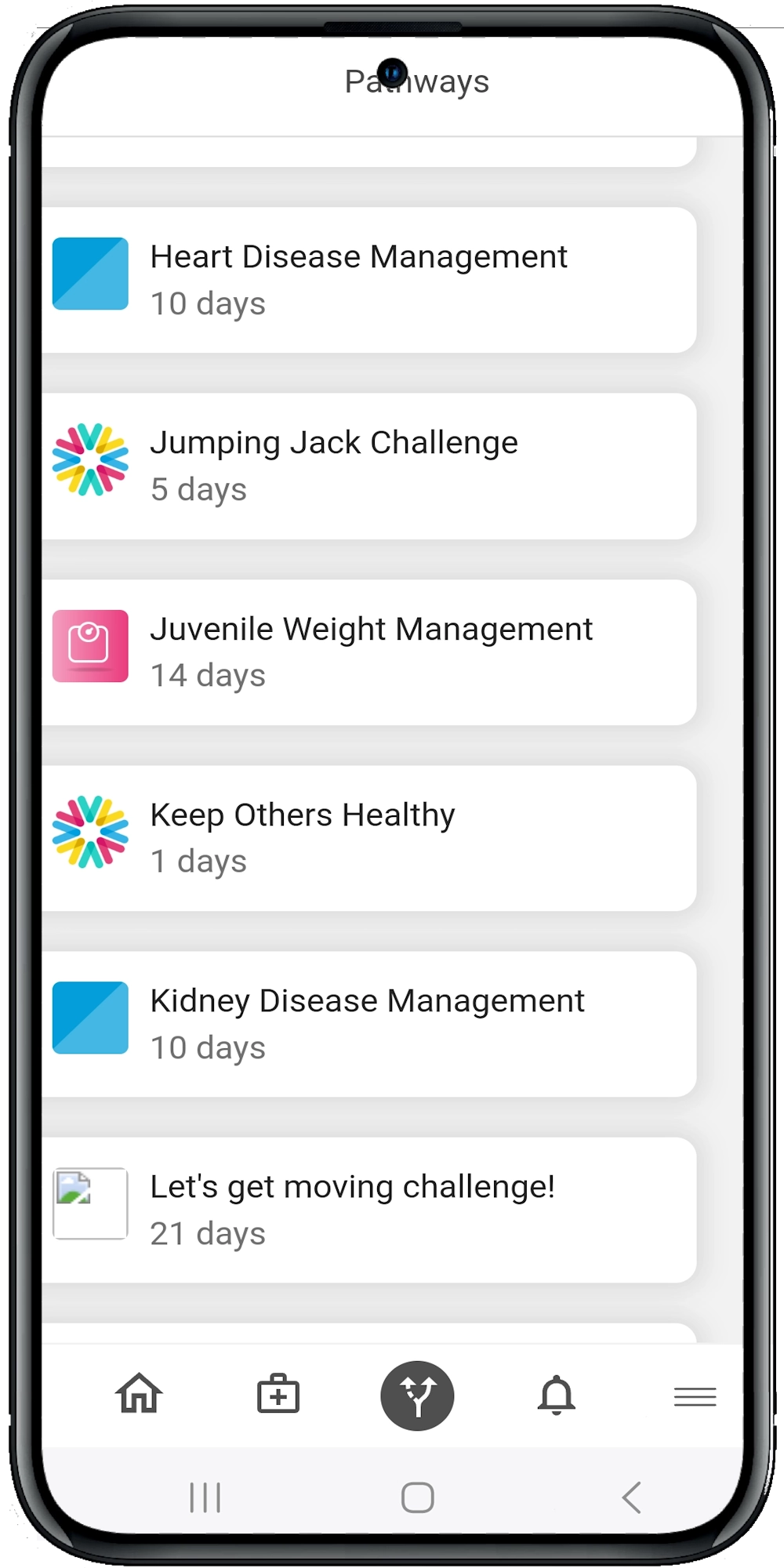

But all of these initiatives live or die by their ability to connect with and engage patients who may be reluctant to take advice from medical professionals, especially from outside their communities. If we’re going to move the needle on low-income health outcomes, we have to connect with people directly through the technology they use every day — their mobile devices.

The Income Barriers to Health

Delivering care to low-income populations — and more accurately populations with low socioeconomic status (low-income, low-education, low upward mobility, and lack of insurance) — is complicated by some deeply human challenges. Obviously, not all people of low socioeconomic status are minorities, but they represent a disproportionate bulk of this group, with the economic gap widening since the 2007 recession.

Though it varies by city and other factors, on average, minority groups have a higher distrust of doctors than their white counterparts. Even though many of these individuals say they’ve seen a physician in the last year, they may not trust that doctor when it comes to

- Their competency to refer them to a specialist when needed;

- Commitment to putting the minority patient’s medical needs above all other considerations;

- Influence by health insurance company rules on the doctor’s decision making; and

- Performance of unnecessary tests and procedures.

The reasons for this distrust are complex but entirely valid. There is plenty of evidence of current and historical inequitable health treatment for black Americans. Meanwhile, one-quarter of Latino adults in the United States are undocumented, making them ineligible for Medicaid and afraid to sign up for ACA health insurance. Add in a language barrier or communication gap, and it’s unsurprising minority groups are wary of the healthcare system.

Cultural norms can come into play as well. Back in 2012, the Census found that 72 percent of Hispanics say they never use prescription drugs. The reason seems to be, in large part, a stronger belief among Latinos in natural medicine and alternative practitioners. When a Hispanic person feels ill, they’re likely to ask their families for home remedies instead of turning to medication.

For all these reasons, bussing mostly white medical doctors and nurses into low-income minority areas won’t help very much on its own. We have to address the trust barrier if we’re going to start driving meaningful outcomes for low-income groups.